Early Modern Women's Marginalia

The Library of Libraries

Attribution

Definition

Attribution is the process of ascribing of marginal marks to agents

The majority of marginalia is anonymous. Frequently unsigned, in hands that cannot be associated with specific authors, and in many cases taking the forms of underlining, crosses and other deictics, marginalia as a corpus is unusually difficult to attribute. There are three ways in which marginalia can be associated with an author.

The first is through signature. Early modern subjects often signed their books, on the front pastedown, fly leaves or title page, in blank spaces within the book, in the margins, or on the endpapers and pastedowns. These signatures, especially when accompanied by longer inscriptions that provide evidence of a broad range of distinctive letter forms, can be linked to other examples of handwriting in order to make attributions. If there is a single marginalist in a book, signature can be used to make reasonably stable attributions. When there are multiple hands, these attributions can be more tenuous, especially when there is a small amount of written material that can be used to compare letter forms and for visual forms such as stars and flowers that are not accompanied by text.

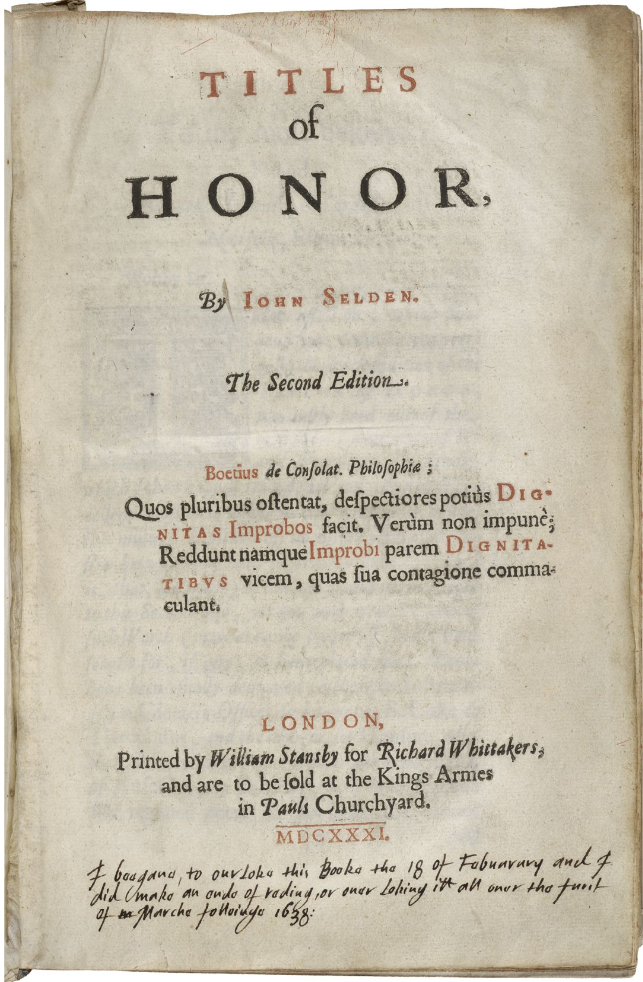

The second way in which an attribution can be made is when a marginalist has a distinctive, known hand. This is the case for famous marginalists such as Gabriel Harvey, and for women who frequently annotated their books in a distinctive style, such as Anne Clifford. Her copy of John Selden’s Titles of honor is not signed, but contains an opening epigraph which is distinctively hers because of its detail of where and when she read the book over, the nature of her annotations, and even the ochre colour of their ink. On the title page is a note that reads; “I beegane to ourloke this booke the 18 of Febuarary and I did make an ende of reding, or ouer loking itt all ouer the first of Marche folloinge 1638.”

Fig. 1. Epigraph by Anne Clifford inscribed in John Selden, Titles of honor and nobility (London: 1631), title page. Marg ID 1014. Call #: STC 22178 copy 3. Image 49729. Folger Shakespeare Library.

The rest of the book is marked on almost every page in a highly distinctive style that aligns with other marginalia by Clifford across a number of texts which she owned.

Attributions can also be made through contextual information. Gift inscriptions can identify a writer even if they are unsigned. A daughter might sign and date a text in ways that allow us to identify her marginalia: ‘This book was giuen to me by my father the Bishop of Worcester 1646’; or a gift inscription might then be linked to other initials in a text that allow an attribution.

Certain kinds of marginalia are easier to attribute than others. Signatures can be relatively securely attributed to women authors, although there are examples where another agent (such as a scribe or a family member) adds a woman’s name to a text. Some annotations, especially if signed, accompanied by initials, or in a hand linked to a signature elsewhere in the volume, can be made with relative security. Visual forms, from small stars, crosses and circles in the margin to elaborate drawings, are more difficult to associate with a specific agent. Occasionally, such forms contain an element of text that can be linked to other handwriting in a volume, but it is always possible that these textual elements could be added to an illustration by another agent.

For our database of early modern women’s marginalia, this creates unavoidable biases. The easiest material to attribute to women – ownership marks – make up 80% of the database. Annotations, marks of recording and graffiti (drawings, doodles, scribble) each constitute around 7% of the database. But it is important to understand that these figures represent the marginalia that can be attributed to women, not marginalia by women. The majority of marginalia that we encounter in texts is anonymous and cannot be attributed to any known agent, male or female.

Visualisation of Marks, sorted by condifence in Female Authorship (Certain, Probable, Possible), and colour coded by type of mark

In order to mitigate these biases while still identifying marginalia by women, the database allows attributions to be made across a sliding scale: Certain, Probable and Possible. In the case of ‘Jane Smith her booke’, the attribution is Certain. If there is other marginalia that is very clearly in the same handwriting, that would also be Certain.If there is only one signature in a book—a woman’s signature—and the handwriting styles are not clearly different, we can attribute all the other marginalia in that book as ‘possibly’ or ‘probably’ by the woman listed. If the other annotations in the book are something non-textual, such as pen trials or underlining, then we would add it as a marginal mark but deem it Possible.If there are multiple signatures in the book, for example Jane Smith and a few other male signatures, a higher burden of proof is required, as we know many people used the book. If the hand of the female signature clearly matches annotations in the rest of the book, then we can use Certain or Probable. If the hands of that other marginalia do not match, we do not include it. If the other marginalia is non-textual, for example underlining, pen trials, or notes so short that we cannot match handwriting styles, then these are not included, as we have no proof that they are by the woman and not by one of the male annotators. Attribution is particularly challenging for marks such as scribble, pen trials, letter practice and smudges and stains. These are included when they are proximate to other marginal marks clearly ascribed to a woman agent and in a similar hand and/or ink, and are classified as Possible.

Visualisation of Marks, sorted by condifence in Female Authorship (Certain, Probable, Possible), and colour coded by each book's publication date

Rosalind Smith