Early Modern Women's Marginalia

The Library of Libraries

Drawing

Definition

Visual marks such as illustrations, copies of ornaments and typography, manicules, stars and flowers as marks of emphasis.

Most scholarship on early modern women’s marginalia to date has concentrated on its verbal forms, yet women’s annotations also include visual marks or images of varying degrees of legibility and complexity, ranging from stars and manicules, doodles, copies of typographical ornaments, drawings in pen and ink, and the insertion of images into texts through cutting and pasting. These visual forms comprise an exciting and largely unexamined sub-corpus within early modern women’s marginalia, providing new evidence of how women read, how they saw their world, and how they used their books. Visual marks also illuminate how women engaged with formal categories of visual expression such as calligraphy, copying and drawing, with implications for our understanding of their education and their relationship to humanism. The drawings found in our database show how important both texts and images were to the ways in which women perceived and represented their worlds.

One important use of image in the margins has been to help readers note and highlight a feature of a text, allowing it to be more easily understood and remembered. Images such as stars and manicules (hands pointing to certain lines) are the most common forms of such visual marginalia, and they add the humanist concept of enargeia (vividness) to a reader’s interaction with the page, amplifying, decorating and ‘colouring-in’ texts not only with marks such as underlining but with images drawn from what the reader saw in the world around them. Women as well as men annotated their texts using such visual aids, as Mary Powntis’s manicules in a copy of The Zodiake of Life show. There are very few examples of women’s use of this kind of visual annotation, but they do exist, showing that women had access to elements of humanist annotation despite their exclusion from the all-male humanist schoolroom.

Fig. 1. Manicule inscribed by Mary Powntis in Marcello Palingenio Stellato, The zodiake of life written by the godly and zealous poet Marcellus Pallingenius stellatus (London: 1565). Marg ID 307. Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, Douce P 584. Image Jake Arthur.

Rather than strict segregation, women’s use of forms such as the manicule to annotate texts and to mark passages show how the education of men and women overlapped. Women as students and teachers can be found at the sixteenth-century schoolroom’s edges, and their levels of literacy and education increased throughout the seventeenth century.

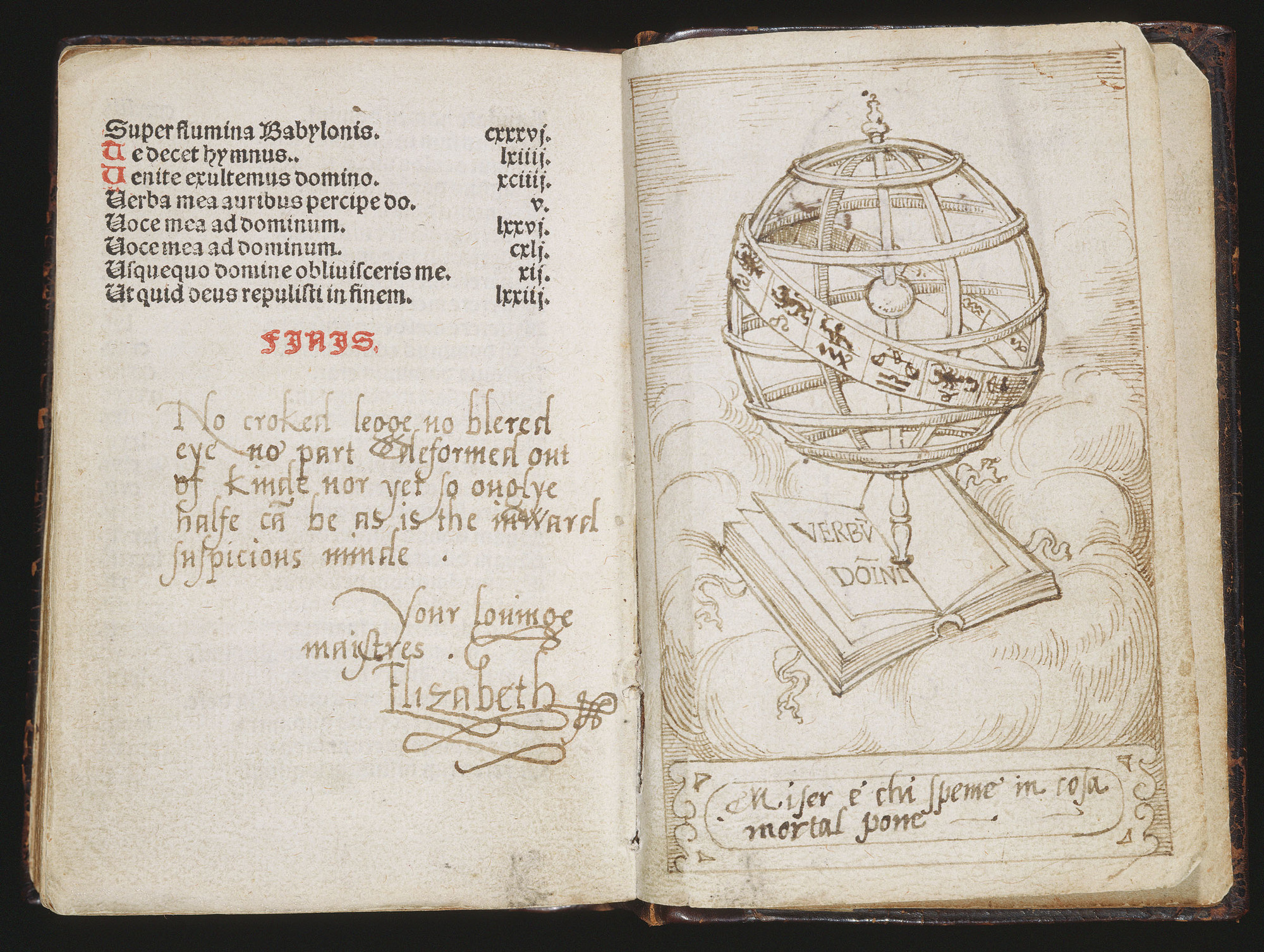

Some women, especially royalty, did receive a humanist education which included instruction in writing, drawing, painting, perspective and geometry. Again, we have very few traces of how royal women acquired and used these skills. One stunning exception is the drawing of an armillary sphere that faces a quatrain by the princess Elizabeth on the final pages of a Book of Hours, where a scroll beneath the image in Elizabeth’s distinctive italic hand contains a line from Petrarch’s Triumph of Death: ‘Miser é chi spemé in cosa mortal pone’ (Wretched is he who places hope in a mortal thing).

Fig. 2. Quatrain, signature and quote inscribed by Princess Elizabeth with armillary sphere probably by another hand in Psaultier de David (no date), Royal Collection Trust, Windsor Castle Royal Library, RCIN 1051956. © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust.

It is not known if Elizabeth drew this image or not, but her inscription means that across the opening image and text work together; the quatrain and its signature adhere to the armillary sphere, the book upon which it rests, and the line from Petrarch in Elizabeth’s hand. This is a collection of visual and verbal annotation to be circulated, a way in which the princess Elizabeth could signal her piety, her desire to be guided by the word of god rather than earthly things, as well as her spirited aversion to the damaging workings of the ‘inward suspicious minde’.

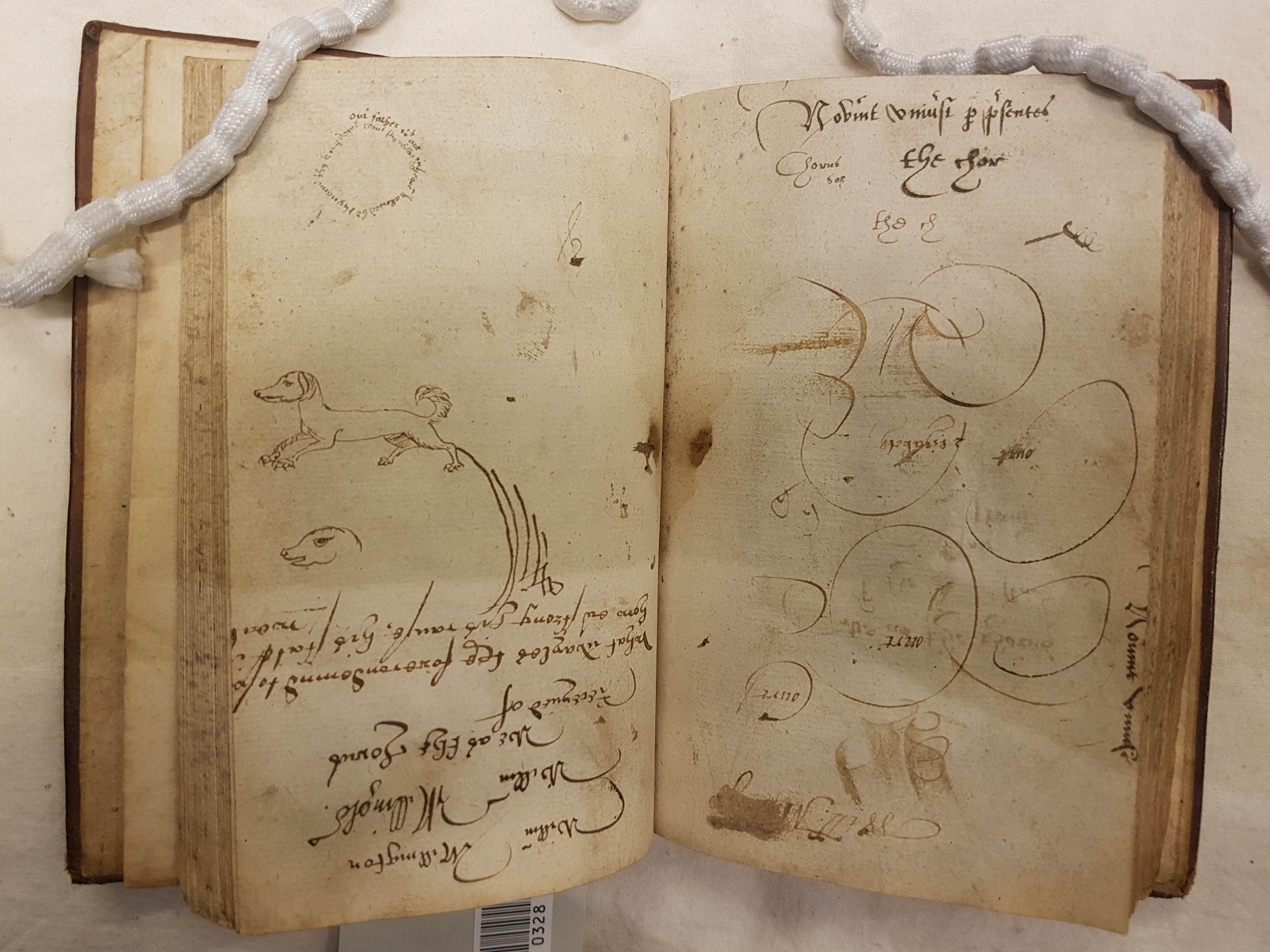

Visual forms can combine text and image in other ways. A copy of Samuel Daniel’s Certaine Small Poems contains the signature of Elizabeth Court, practised with exaggerated circles common in writing manuals. The same hand writes a tiny, circular Pater Noster in the corner of this page opening, a mechanism for meditating upon and digesting the prayer in the act of writing.

Fig. 3. Signatures, drawings and circular paternoster by Elizabeth Court in Samuel Daniel, Certaine small poems lately printed : with, The tragedie of Philotas (London: 1605), blank leaves inserted after sig. F6v. John Emmerson Collection, State Library of Victoria, RAREEMM 322/21. Image Rosalind Smith.

Visualisation of Types of Drawing, sorted by drawing type, and colour coded by each book's date of publication

Rosalind Smith