Early Modern Women's Marginalia

The Library of Libraries

Reading

Definition

Marks of active reading including comment, underlining, emphasis, symbol (such as flowers, crosses, dots, even the imprint of a nail) and marks indicating revision, correction and translation.

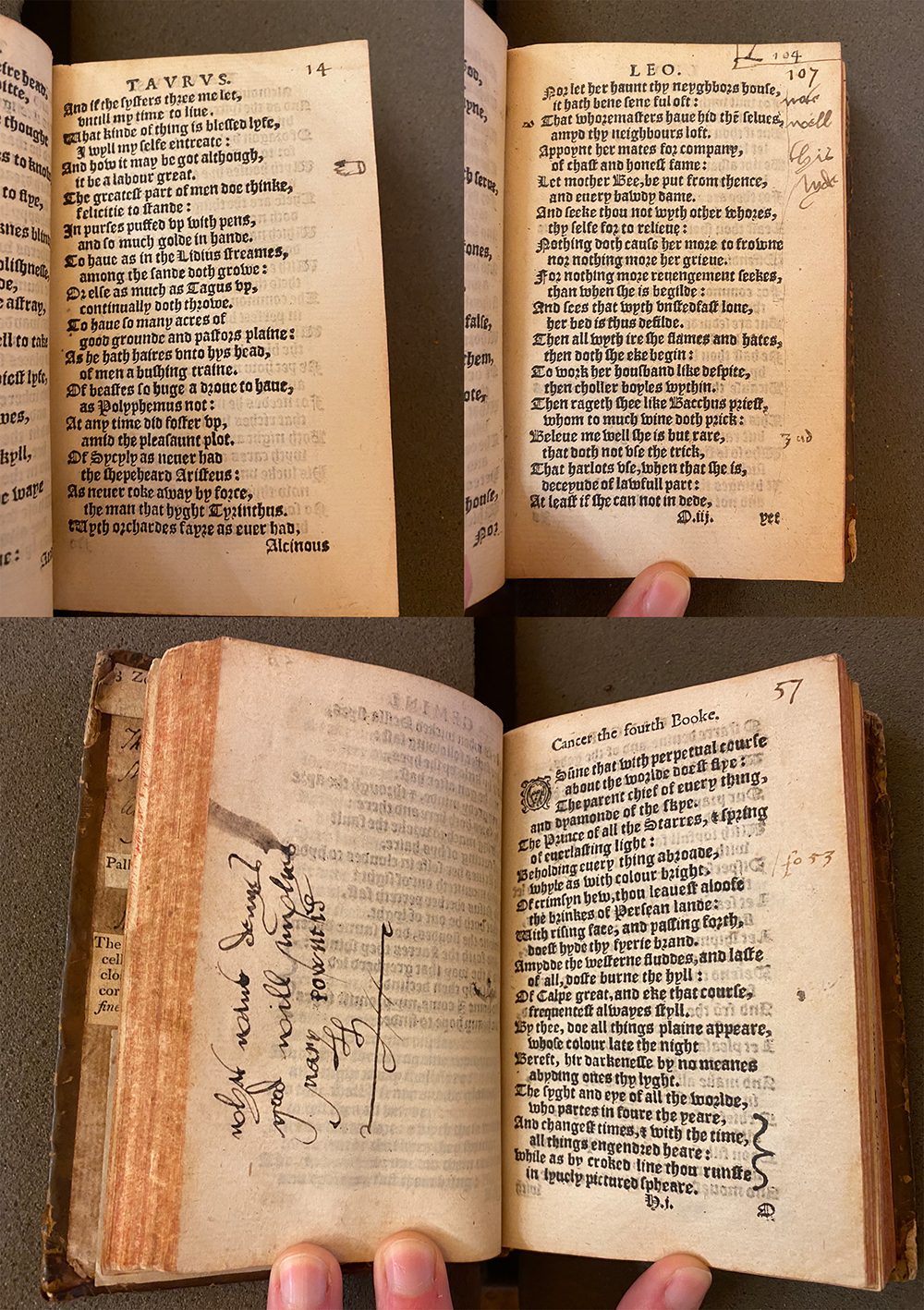

Marginalia is a rich resource for tracing women’s reading practices, showing what interested them, what they wanted to emphasise and remember, how they made connections between texts, and how they altered texts to increase their comprehension or the text’s clarity. However, marks of active reading are often difficult to associate with a specific agent, as books bear the traces of many readers, and the marks that indicate reading are often not in the letter forms that allow marginalia to be matched to signatures and associated with a woman agent. This is particularly difficult for marks such as the indentation of a nail, which women and children were encouraged to make before, or in lieu of, acquiring skill in penmanship. Nonetheless, the database does provide examples of women’s active reading, which constitute just over 20% of all marks found. At one end of the spectrum are marginalia by elite women readers such as Lady Anne Clifford, who not only recorded when and where she ‘read over’ her books but also intensively underlined and marked passages as she read. The project has also found less well known, and possibly non-elite women reading in similar active ways. Mary Powntis annotates her copy of The Zodiake with manicules (images of a pointing hand) highlighting key passages, underlining and comments such as ‘note this’. She copies aphorisms from the text and adds new material in the style of the texts that she reads, demonstrating her familiarity with its forms and models.

Fig. 1. Marginalia inscribed by Mary Powntis: a) manicule used for emphasis; b) highlighting and comment, “note well this syde”; c) a pious rhyme and a curly brace used to highlight text. In Marcello Palingenio Stellato, The zodiake of life written by the godly and zealous poet Marcellus Pallingenius stellatus (London: 1565), sigs O3r, G8v-H1r . Marg ID 307, 310 and 311. Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, Douce P 584. Images Jake Arthur.

Other women marginalists mark passages with terms such as ‘Mind’, showing, for example for Anne Mansell, that particular lines from the sonnet sequence Astrophil and Stella are to be particularly noted. Other evidence of reading by women consists of the intertextual references that show readers connecting their texts with others. This practice occurs most frequently in religious treatises that are linked to passages in the Bible, and show women applying humanist models of textual comparison to their devotional reading. Where marginalia are positioned can also provide evidence of reading. For example, when Mary Queen of Scots places a quatrain of her poetry beneath an image of King David at prayer in her Book of Hours, she shows her understanding of David’s authority as a godly sovereign and the impact such an association will have upon her own writing as a sovereign. At such times, the line between textual addition and readerly annotation is blurred; the marginalia simultaneously denotes reading and writing.

Other examples of women’s reading are evident in the corrections, revisions and translations made in the hands of identifiable women agents. Again, these can be authorial, as in the corrections made by Margaret Cavendish or Lady Mary Wroth to their own texts in print and manuscript. Reading over a passage, they suggest improvements, revisions, or strategic emendations for local political effect. Translations of key words across a text also show women’s reading practices, as they render difficult or unfamiliar words into a first language.

Visualisation of books, sorted by types of marks made, and colour coded by each book's date of publication

Rosalind Smith