Early Modern Women's Marginalia

The Library of Libraries

Recording

Definition

Any textual mark recording information that is not related to the text, using the book as convenient paper stock for other, unrelated information. Marks of recording include accounts, prices of goods, lists of dates, calculations, recipes, poems and letters unrelated to the book’s contents.

Recording is one of the less common forms of marginalia found in books, but there is a pattern in the kinds of records we do find. These records appear most often on blank frontpapers and titlepages, but have been found scribbled in the margins, or written next to pertinent passages of printed text related to the recorded information.

One form of recording found in extant early modern books, and certainly of the more formal kind, is family records. Most often, this includes the birth and/or death dates of family members, with some books including information such as marriage dates, and others appearing as larger family trees.

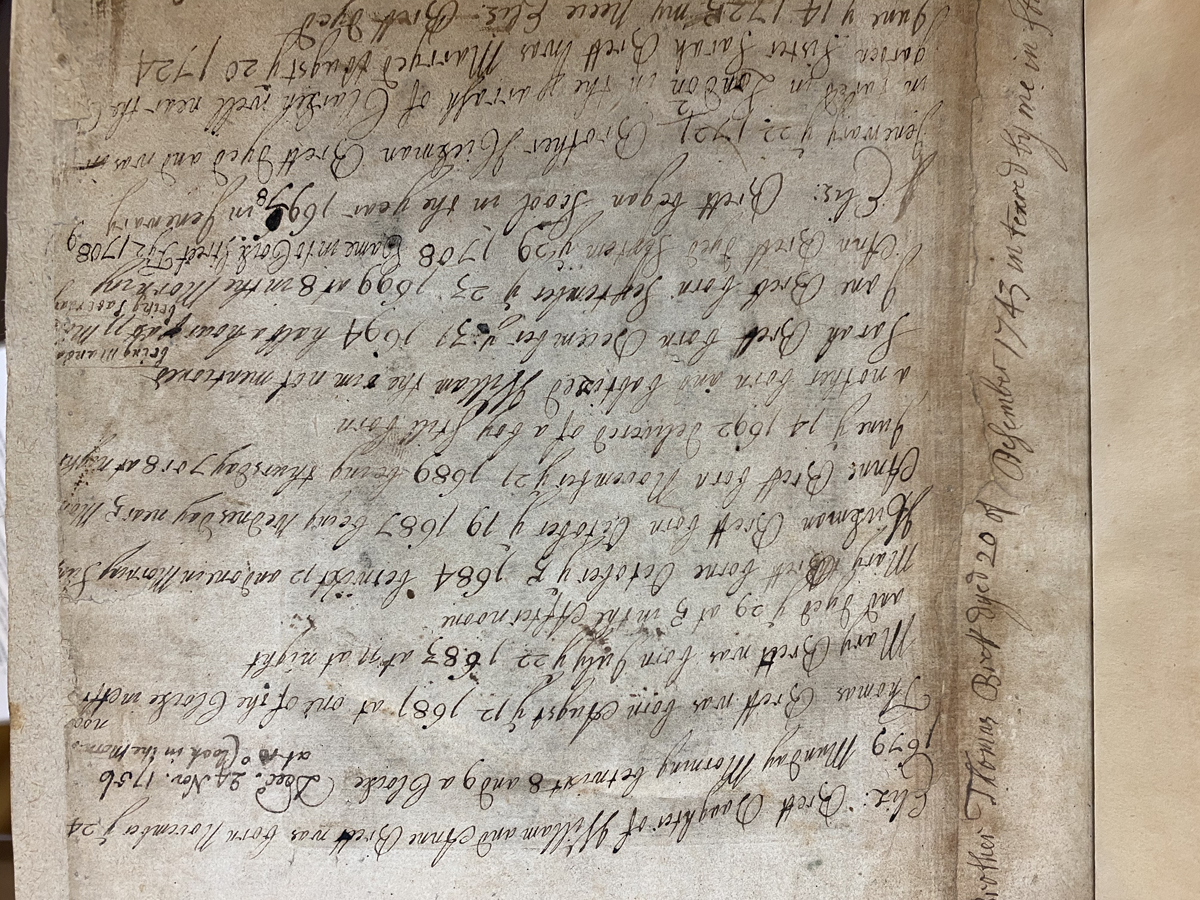

Fig. 1. Detail of a ledger of family events including births, deaths and marriages from 1679 to 1759 inscribed in Bible and The book of common-prayer (Oxford, 1682), front flyleaf. Marg ID 107. Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, Bib. Eng. 1682 c.1 (1). Image Jake Arthur.

Family records are most often found in large folio texts, mostly Bibles, and seem to be intended as a form of historical record for users of the text. The familial inheritance implied through the recording of family history in this way illuminates how books are used within communities of readers, and how important shared knowledge is within these groups. These self-contained archives can also be seen as an educative tool whereby descendents of the book owner who first recorded their family history can learn the names and dates related to important family members and events, and continue recording similar life events in the future.

Early modern book users also recorded when a book had been given, or gifted, to them. Gift records are an extension of ownership marks, where marginalists both identify themselves as the current owners of a volume, and the circumstances through which they came to own it. We see evidence of books passing from husbands to wives, mothers to daughters, fathers to daughters, and, of course, between friends.

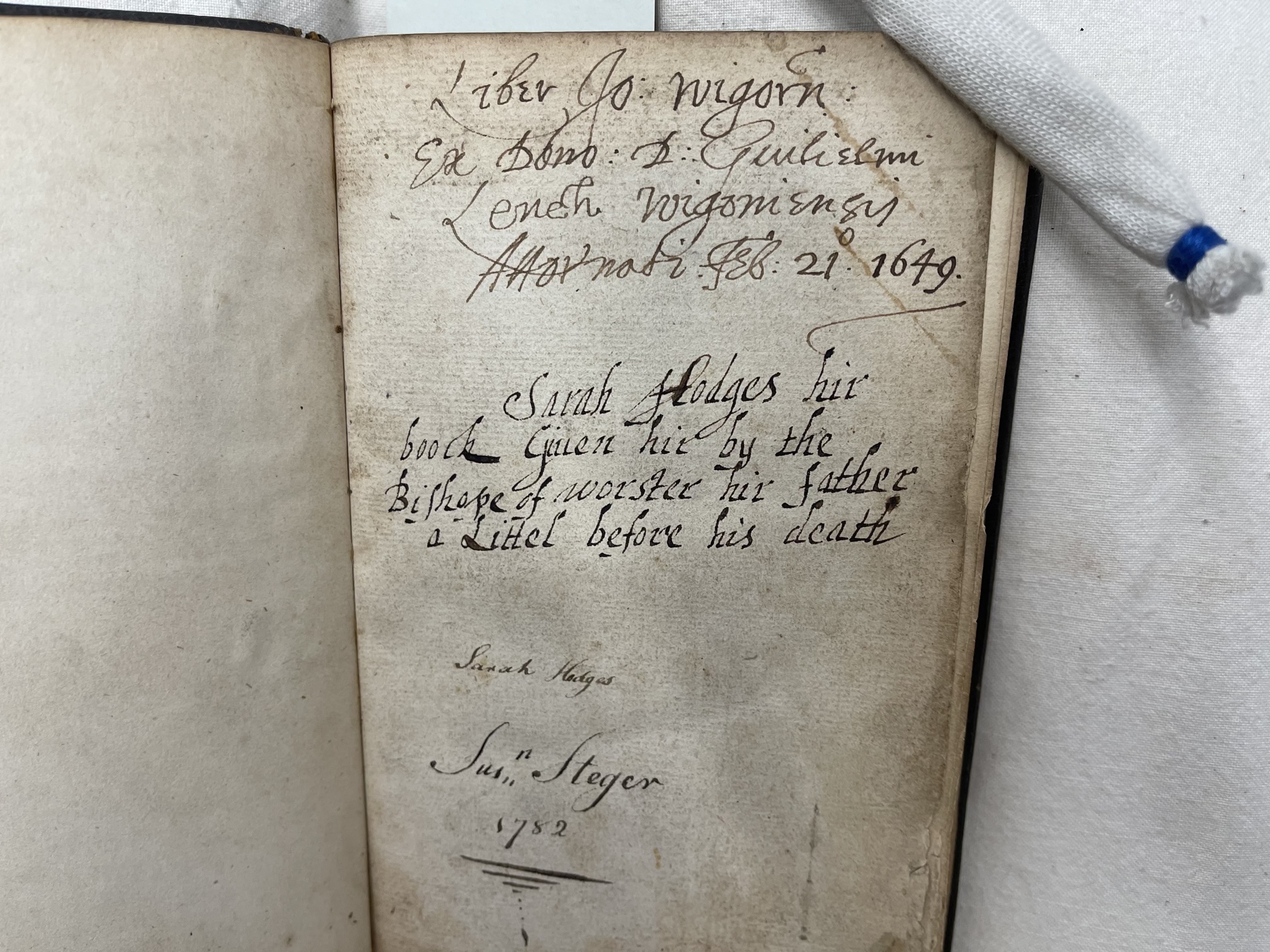

Fig. 2. Gift record inscribed by Sarah Hodges in John Gauden, Eikon basilike, the pourtraicture of His Sacred Maiestie in his solitudes and sufferings (London, 1648), front flyleaf. Marg ID 781. John Emmerson Collection, State Library of Victoria, RAREEMM 122/2. Image Rosalind Smith.

Similar to family records, gift records are useful as they help us to reconstruct women’s relationship to texts even if these books are not recorded as part of formal libraries, or bequeathed to women in wills. As we attempt to reconstruct lost, or overlooked, parts of early modern women’s history, this kind of marginalia is an important tool to help fill in gaps that more formal legal records may have left when it comes to books as women’s property.

Records of accounting also feature on the blank pages of books, though less often than other examples mentioned. These also fulfil an archival function as the marginalist makes a note of a transaction that is important for them to remember. Though she does not note what the sum refers to, Margaret Barnard, for example, recorded this in her Bible:

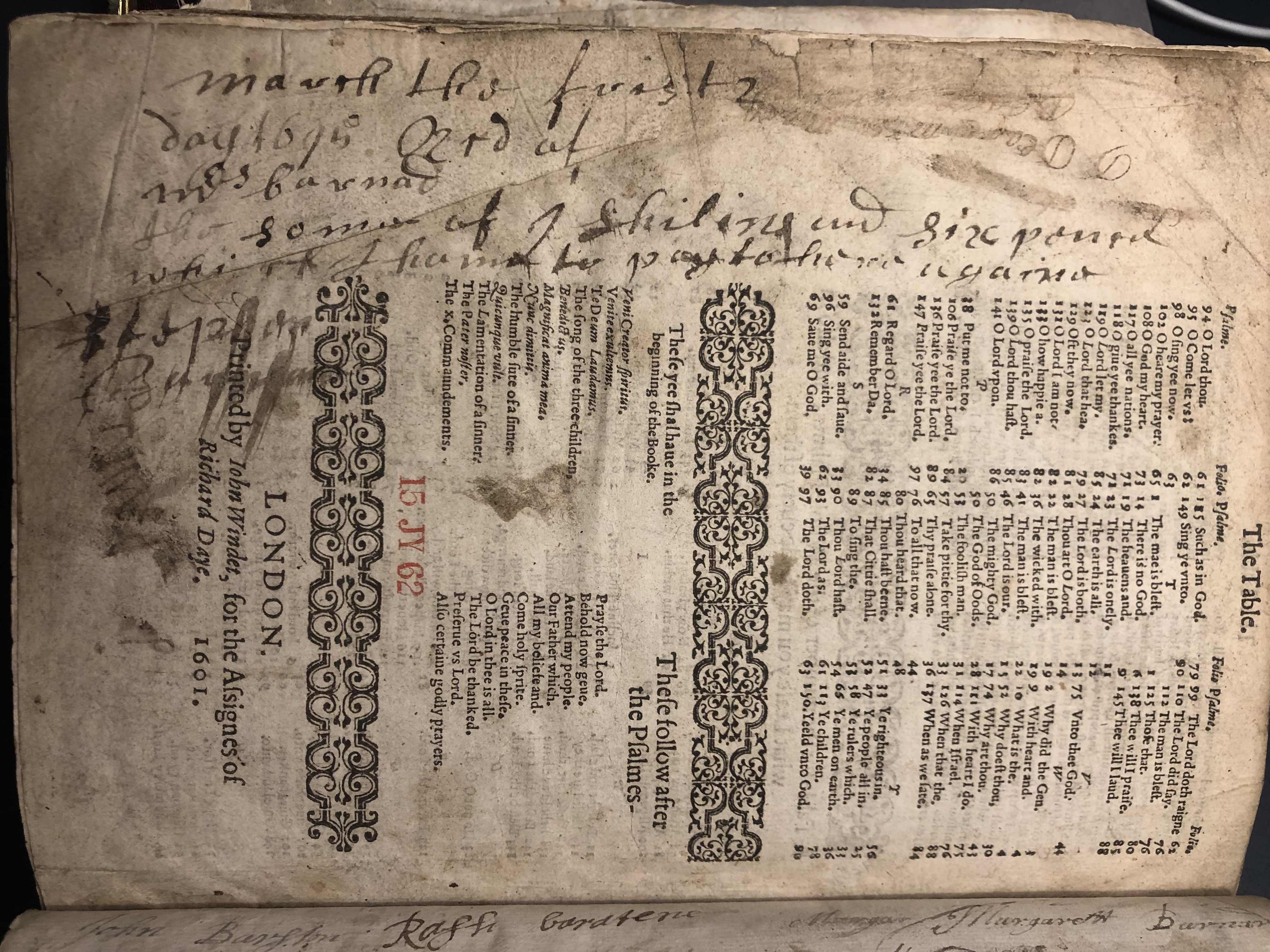

Fig. 3. An accounting record, “march the first 2 day of 1695 22cd at m[istress] Barnad the some of i shiling and six pence which I have to pay to here againe,” inscribed by Margaret Barnard in The Bible, etc. (London, 1601), p. 102. Marg ID 357. British Library 3052.cc.9.(2). Image Hannah Upton.

These marks are interesting to consider in terms of women’s education, where, when numeracy is mentioned as a subject learned by early modern women, it is often in terms of accounting. Most records of women’s dealings with accounting come from manuscript account books kept by early modern women, so these examples found in the margins indicate a perhaps less formal way of recording transactions, and the re-use of book pages within the home as paper to be written on during the early modern period.

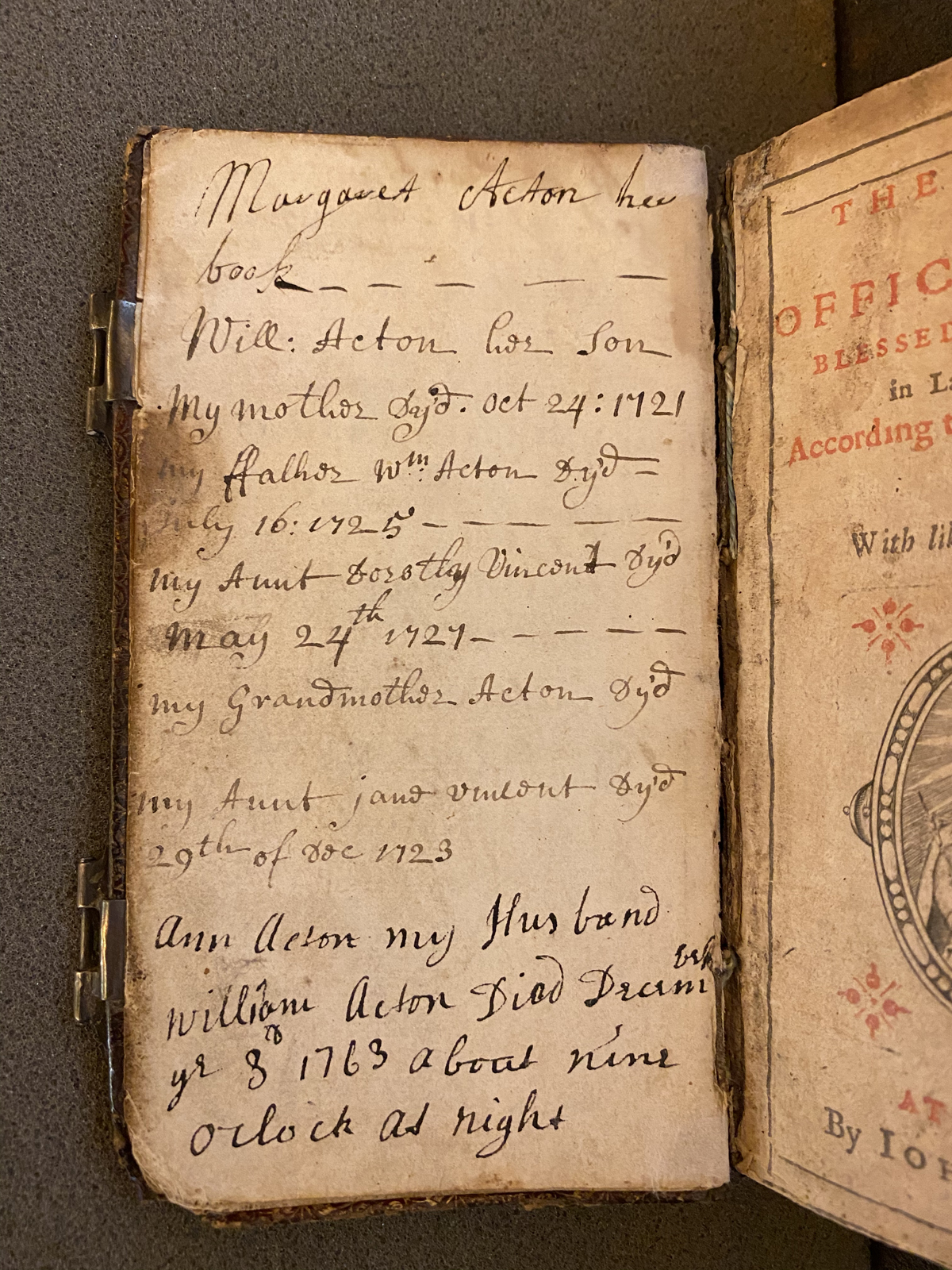

Recording is a more difficult form of marginalia to work with, as family records and accounts are often unsigned, and can be written in multiple hands. Despite family records, in particular, being listed by scholars as a common form of marginalia, less academic writing has been dedicated to them, possibly due to this attribution issue. There is a primer, for example, that has a written record of family death dates from the seventeenth century onwards, but as the only signatures that appear, of a Margaret and an Ann Acton, date from the eighteenth century, it is difficult to know who composed them:

Fig. 4. Record of family dates inscribed in The primer, or Office of the Blessed Virgin Marie (Saint-Omer, 1621), front flyleaf. Marg ID 48. Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, Lawn f.158. Image Jake Arthur.

Accounting has a similar issue, where lack of signatures means most examples are listed as ‘Possible’ instances of women’s marginalia on our database. This does not mean that these markings are insignificant; the potential for women’s involvement in this kind of recording is a worthy avenue of investigation in and of itself, and we often have examples of other forms of women’s book use in the same volumes. It does mean, however, that we must be careful when making generalisations about which forms of marginalia are ‘common’, and the role women may have in composing them. What we can get insight into from these examples, definitive attribution or not, is women’s role within literary communities and the implicit sharing of knowledge through the sharing of books, and by extension the marginalia contained within them.

Early modern women’s marginalia provide evidence for how women used their books as spaces for writing. Often overlooked in studies of marginalia, this is a rich source for women’s marks in books and ranges literary forms, such as poems in fair copy, to accounts and recipes. William Sherman coined the term the ‘matriarchive’ for such uses of the book as a compendium of resources, and marginalia studies more generally have begun to turn towards writing and away from reading in considerations of the manuscript and print elements of a book as synchronous and equal. Some of the most beautiful and historically significant marginalia in our database belongs to this category, including a suite of poems by Mary Queen of Scots added to her Book of Hours. Other women recorded family lineages in their bibles, and others added details of life events in the blank spaces of their books.

Visualisation of Marks of Recording, sorted by recording type, and colour coded by each book's date of publication

The most common instance of recording across the database is the addition of fragments, lines and copied passages from other texts. This is also evidence of reading, although not always directly of the text at hand, and of the ways in which marginalists connected the texts they read through commonplacing. One of the most significant women book owners in the early modern period, Frances Wolfreston, adds poems excerpted from Francis Quarles’ books to her edition of Charles Hammond, The worlds timely warning-peece newly corrected and amended:

Fig. 5. Poem excerpts from Francis Quarles's Divine Fancies (1632) inscribed by Frances Wolfreston in Charles Hammond, The worlds timely warning-peece newly corrected and amended (London, 1660), p. 16. MargID 2500. British Library, Cup.408.d.8.(4.). Image Hannah Upton.

Hannah Upton